Next: Factor 3 - Reproducibility of AI Innovation

Previous: Factor 1 - Nature of AI Innovation

This article forms one part of a broader decision framework for evaluating whether patent or trade secret protection is appropriate for AI innovation.

The framework is designed to help decision-makers (e.g., innovators, in house, CTOs) align patent and IP strategy with underlying business realities and moving beyond purely "legal" considerations.

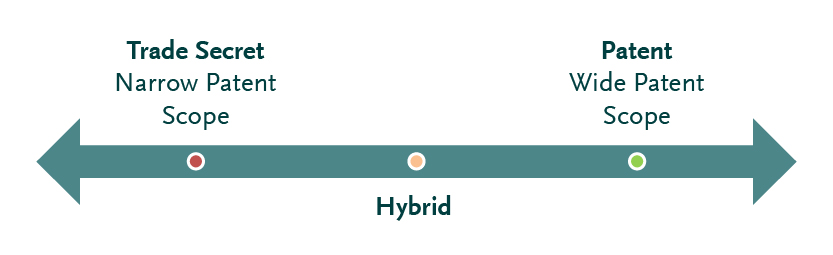

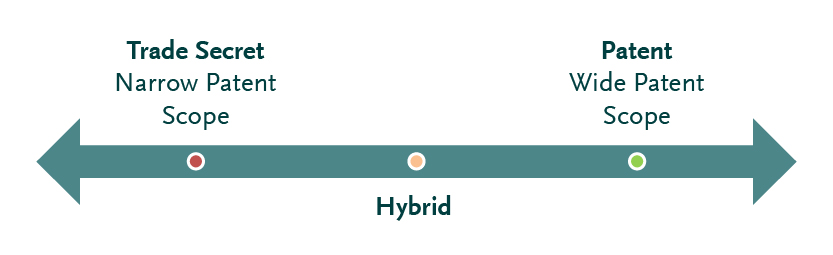

Within that framework, this article addresses a second decision factor: what is the realistic patent scope for the AI innovation?

An AI patent with meaningful scope can block competitors from implementing commercially viable alternatives. Assessing enforceable scope therefore requires focusing on some of the following factors: (a) competitor blocking potential; (b) detectability of infringement; and (c) divided infringement.

a. Competitor Blocking Potential

If the AI patent scope is too limited, competitors may be able to design around the patent with little effort while still benefiting from the disclosed ideas. That said, narrow scope patents can still be valuable where the inventor has identified a highly valuable and specific combination or configuration that competitors are likely to adopt.

|

Examples: Competitor Blocking Potential

- Patents (High Competitor Blocking)

As noted in the previous factor, patents that emphasize the overall functional outcome and system-level use of AI tend to offer stronger competitor blocking because the scope of protection is wide and covers a broad application (e.g., big picture AI innovation).

- Trade Secrets (Low Competitor Blocking)

Patents that are narrowly tied to specific technical AI implementations provide weaker blocking potential (e.g., small picture AI innovation). This is because competitors can avoid infringement by making modest technical adjustments to the implementation, while delivering similar functionality. Having said this, patents directed to specific technical implementations may still be valuable where those implementations are particularly effective and therefore likely to be sought out or emulated by competitors.

- Hybrid Approach (Patents/Trade Secrets)

A patent may be used to protect overall function and system-level use. Further, narrow technical AI implementation details (to the extent not required for patent enablement requirements), may be protected with a trade secret.

|

b. Detectability of Infringement

AI patents have limited enforceable value if infringement cannot be practically identified or enforced. Where AI innovation is externally observable/detectable in a competitor's product or published material, patent protection is often viable. Where detectability is low, trade secret protection may be the more effective option. The deployment environment, such as cloud-based, local or edge deployment, plays an important role in determining how easily infringement can be detected.

|

Examples: Detectability of Infringement

- Patents (High Detectability)

Infringement is more readily detectable where the AI innovation is of a type that, if adopted by a competitor, would be deployed in a way that allows its use to be observed or evaluated. This includes innovations that would normally be implemented in edge-deployed systems or other user-facing products and applications, and that can be assessed through direct product analysis or input–output testing. In some cases, the nature of the innovation is such that its adoption would also be reflected in a competitor’s public disclosures, such as promotional materials or user documentation.

- Trade Secrets (Low Detectability)

By contrast, detectability is lower where AI functionality is embedded within opaque or distributed systems. Where models are deployed exclusively in backend or cloud environments, where inputs and outputs are heavily abstracted, or where public disclosures are limited or vague, it becomes more difficult to evaluate how the AI operates. In these situations, infringement may be difficult to detect or prove, even where similar functionality is suspected.

- Hybrid Approach (Patents/Trade Secrets)

In some cases, an AI innovation includes both observable and non-observable elements. The externally visible aspects of the system, such as user-facing behavior or high-level functional outcomes, may be detectable if adopted by a competitor and therefore suitable for patent protection. At the same time, internal implementation details that operate within backend or cloud environments may remain difficult to observe and are less readily detectable. This mixed detectability supports a hybrid approach.

|

c. Divided Infringement

AI systems are often distributed across multiple parties. For example, one party may train the model (e.g., developer), another may host it (e.g., cloud service provider) and a third may deploy it within a product or service (e.g., customer). This creates a risk of divided infringement, where no single party performs all steps of a patented method, making enforcement difficult. Although workarounds exist to catch divided infringement, they are complex and uncertain. Patent claims are therefore most effective when they are performed by a single party, and where that party is ideally a competitor rather than a customer.

|

Examples: Divided Infringement

- Patents (Low Probability of Divided Infringement)

The patent scope is focused on a single locus of activity, such as model training alone, or model deployment alone. Alternatively, it's focused on both, however each provides standalone innovative value.

- Trade Secrets (High Probability of Divided Infringement)

The innovation and patent scope spans both model training and model deployment. In practice, these steps are often performed by different parties, such as a technology provider that trains the model and a customer that deploys it.

- Hybrid Approach (Patents/Trade Secrets)

The patent scope is directed to multiple system-level AI capabilities that can each be implemented and controlled by a single party (e.g., platform provider or service operator). For example, training-related and deployment-related functionality are each separately novel.

More granular interactions between training and deployment, which in practice may be split across multiple actors, are not relied upon for patent enforcement and are instead maintained as trade secrets. For example, detailed processes for updating a model based on deployment feedback, such as how user data is selected and incorporated into retraining. In certain cases, this may require coordination between a service provider and customers and are therefore more likely to be split across multiple actors.

|

Applying the Decision Tool: Patents or Trade Secrets

For a further discussion of the decision framework and remaining decision factors in the framework, please see the following:

Framework: Patents or Trade Secrets

Factor 1: Nature of AI Innovation

Factor 3: Reproducibility of AI Innovation

Factor 4: Business Delivery Model

Factor 5: Commercial Longevity

Factor 6: Competitor Defensive Positioning

Factor 7: Patentability Potential and Layered Strategies

If your organization needs assistance evaluating which aspects of its AI innovation are better suited to patent protection versus trade secret protection, our team can help. Our team can also support patent filing and the development of a broader IP strategy.